Image by Dmytro Sheremeta, Shutterstock

“SOS” is probably the most commonly-recognized distress signal on land, sea or in the air. Oftentimes considered an acronym for “Save Our Souls/Ship,” in reality that sequence of Morse Code’s three dots-three dashes-three dots is simply the internationally agreed-upon way to easily remember and transmit those patterns.

To be effective in the wild, an emergency signal must attract attention either through sound (audibly) or sight (visually). Each has its most optimum applications when used in environments that provide the most contrast between the type of signal and the surroundings against which it will be heard or seen.

Audible signals should be loud and shrill enough to reach above the din of the signaler’s surroundings. Yelling is typically the initial signal a victim uses to attract attention (as well as releasing frightful tension). However, the dynamics of one’s voice and the limited time one can continue shouting at higher, longer volumes is very constraining. An emergency signal whistle is one of the best distress sound producers of prolonged and effective noise one can carry along and utilized most anywhere.

Blasts from a high decibel whistle (120 dB +/-) can be heard over long distances. Their effectiveness and optimum sound production is affected by the air (moisture content, temperature, wind direction and velocity), through which the sound waves must pass between sender and receiver. Most important, the whistle can be blown at full volume for hours on end, at high intensity/volume compared with stressing out one’s vocal cords after a short time of strenuous shouting.

Three sound blasts in succession is internationally recognized as a distress pattern — and can be created using gun shots, signal horns, or other distinct sound-producing devices.

Image by Dmytro Matsiuk, Unsplash

The options for visual signals are more plentiful and varied, from ground symbols, to waving colorful pieces of clothing used for flagging, to a variety of aerial pyrotechnic flares, smoke bombs and water dyes. Here’s a quick look at these basic methods of sight signaling.

Ground-to-air symbols can be as simple as an “X” laid out on the ground: dark evergreen boughs against snow; stomped down grass/vegetation in a field, driftwood on a beach (where a distinct pattern, manmade shape may stand out more against the random piles of tide-deposited tree trunks and branches), or the recognized symbols used by air SAR personnel that convey specific needs/info to a rescue pilot overhead.

Here’s a vital tip: Use a waterproof marker to draw a few basic symbols on a piece of outdoor gear (backpack flap, sleeping bag panel, etc.) so you have them with you without needing to remember what specific message each signal conveys).

A set of three signal bonfires can often be seen well from above or over long distances. Having quick-to-ignite fires ready at all times should be part of your rescue signal protocols.

The most important aspect of any ground-to-air symbol is it’s size; it’s dimensions of each segment/leg of the symbol proportionate to the full size on the ground and its “see-ability” from above. A ratio minimum of 5:1 is the recommended proportion for a signal to be able to be seen clearly from the air. That sign should be five times as long as a segment is wide (three feet being the minimum width for any segment/line that is used to create the sign). For example, a trench in the snow used as part of a ground signal needs to be at least three feet wide to be seen from even a low-flying search plane overhead. At the required five-to-one ratio, each full trench symbol (an “X” for example) should be at least fifteen feet long.

Image by Dudarev Mikhail, Shutterstock

Smoke flares are the highest visible signals to use by day; they are bright, can be seen from afar and following their wind-blown trail through the air, rescuers can follow that stream back to its source — you! Marine dye-markers also reveal themselves in pretty much the same way in water.

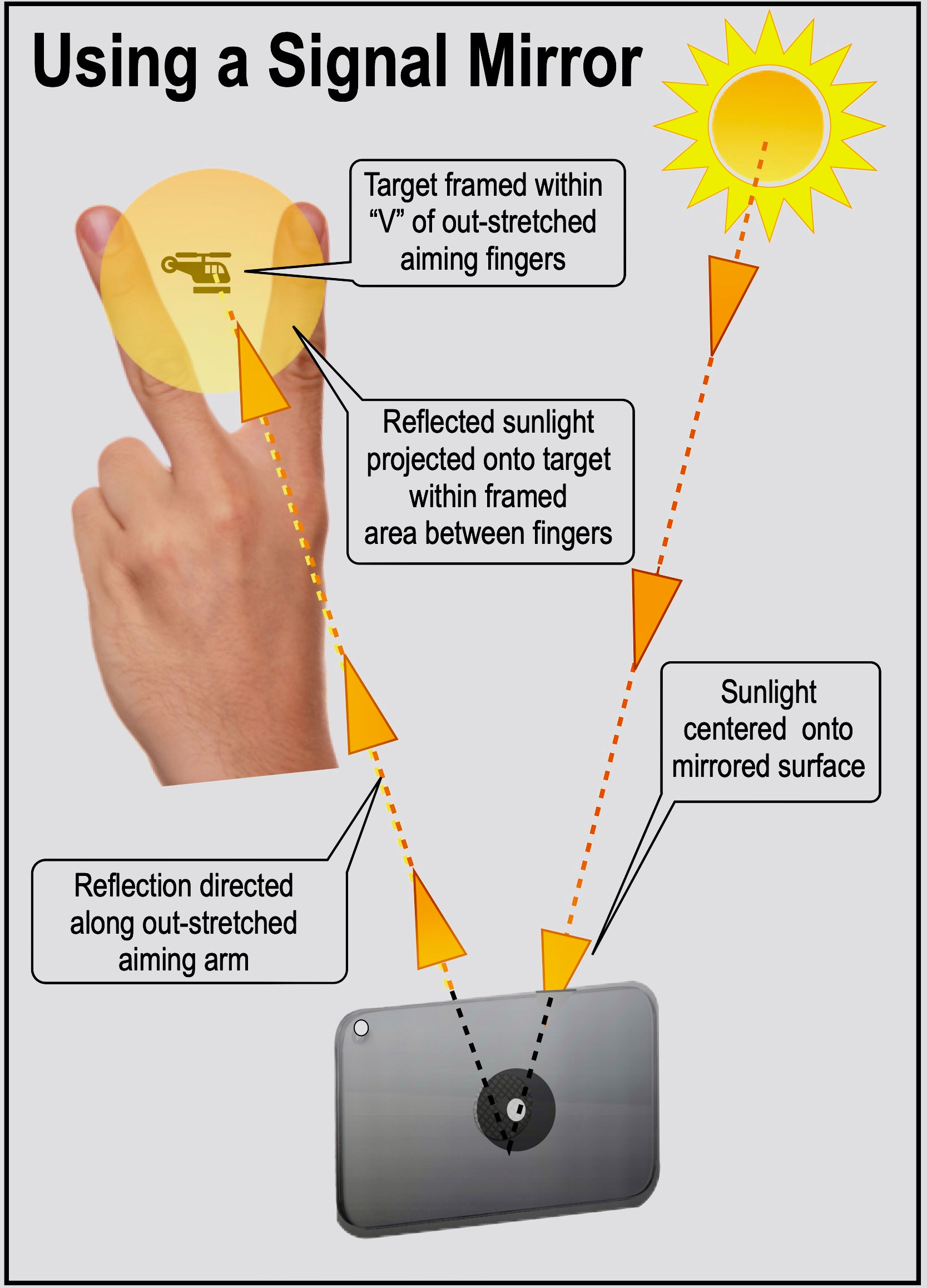

Emergency signal mirrors can be used to send a bright spot of light to a rescuer from many miles away, including distance aircraft. Sighting in the aircraft between the “V” made by the figures of your outstretched hand, lets you aim a beam of sun-light through your fingers and out to the aircraft — like aligning a target through the sights on a rifle.

Illustration by Tom Watson

Night time/low light signals are those that produce a bright light, either from a road flare type of device or an aerial rocket flare. Size and effectiveness vary greatly among flare options. Firing flares in gradually descending height capabilities can help the user draw in a search vessel as each smaller flare highlights a tighter search area.

Another visual signal is simply flagging/waving brightly-colored material (tarp, rain jacket, PFD, etc.) overhead. The color and the motion can be used to draw attention to yourself. When choosing gear and wardrobes for the field, consider the visibility color factor each could present when used as a signal in various lighting conditions.

Patterned noise above the surrounding din, contrasting colors or patterns against a competing background, and eye-catching movement against a contrasting background are all ways at making yourself more visible when signaling in most emergency situations.

Tom Watson is an award-winning outdoor safety and skills columnist and author of guide books on tent camping, hiking and self-reliant survival techniques. His website is www.TomOutdoors.com.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices