Probably one of the most difficult things for a compass user to understand and apply in a real-world situation is magnetic declination — because even if s/he understands the overarching concept, it’s critical to know how to actually deploy the technique to your wilderness navigation. Adding to its difficulty, for those of us who travel across the U.S. or even internationally, the magnetic declination that’s applied changes over time as well as from location to location — so what I see in my home along the Blue Ridge Mountains is going to be different than what someone in the Ozarks or Yellowstone National Park would see.

This guide to understanding magnetic declination is part of a series of articles that help to shed some light on an oldie but goodie technology … the compass. While this tool is over a thousand years old, it is still a handy item to master to keep from getting lost. This series covers the following discussions: (1) Compass Selection; (2) Using an Orienteering Compass; (3) Cell Compass Apps; (4) Declination; (5) Map Reading; (6) Map and Compass.

Part 4: Magnetic Declination

What is Declination?

Before explaining declination, it is best to clarify the two points that are used to define it in a map-and-compass setting. One of those points, the geographic north pole, will not change in our lifetime. The geographic north pole is the northern of two points on the surface of the planet through which the Earth’s rotational axis passes. The second point is the magnetic north pole, which is different from the geographic north pole. The magnetic north pole is generated by the magnetic field of the planet, which is caused by the magnetic properties of the core of the Earth.

Though there are other meanings to declination, when referring to the use of compasses, this word is most commonly used to indicate the difference between true (geographic) north and magnetic north. Declination is measured as an angle, and the typical unit of measurement is degrees. It is measured from any location on the surface of the planet.

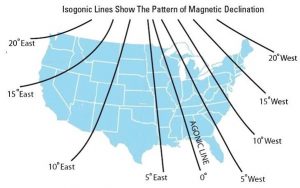

Depending on where you are standing on the globe, there is a value of declination that represents the difference in perspective at your location, the perspective between the direction of true north and the direction to magnetic north. For example, standing somewhere in the eastern United States yields a perspective whereby the location of the magnetic north pole is actually west of the geographic north pole. Declination is then referred to as westerly or negative. Around the middle of the country, or the Mississippi River valley, your compass will still point towards the magnetic north pole, which happens to line up close to the geographic north pole. Declination is, therefore, minimal, and may be zero. The line where declination is zero is called the Agonic Line. If located west of that line, the declination is then to the east (or positive). There are also diagrams of the isogonic lines around the world, which can be quite interesting. That can be confusing, especially for the beginner navigator. This will be clarified further down in the article.

Does Declination Change?

Unfortunately, yes, it does. Declination values change throughout the United States, across the world, and through time. The location of the geographic north pole will not change in our lifetime. The magnetic north pole, however, does change. The core of the Earth, and subsequently the location of the magnetic north pole, are dynamic; they are always changing. As that reference point is slowly changing over time, so is the angular difference from any perspective on earth between the geographic north pole and the magnetic north pole.

While the changes are slow, they are enough that we can see that flux result in the declination for a location change by several degrees over a human lifetime. For that reason, maps need to be updated every decade or so.

How Does Declination Affect My Compass?

Compasses are made to point to the magnetic north pole. At any time, without a map, the compass can be used to find or follow a direction relative to magnetic north (and assuming it works properly).

The principal way declination affects the use of a compass is when the compass is used in conjunction with a map for navigation. Getting an accurate bearing from one point to another on a map requires compensating for declination. It is necessary to know the declination for a particular area. The value of declination can be found on higher quality maps, but it may be outdated. It is best to look up the current declination for your area, which is discussed below in the “Converting” section.

Maps are usually made so that the top of the map is oriented towards geographic north. There are certainly exceptions, such as popular trail maps (e.g. Appalachian Trail) that are oriented in ways to maximize the length of the trail on the map.

East is Least and West is Best … Right?

There are several pneumonic devices used to help people try to remember how to compensate for declination. Some include the heading of this section, and others include majors and generals. Most of these tricks are oversimplified, and do not account for the manageable complexity of the variables that affect the process of accounting for declination in all areas. They can be useful for localized implementation, but here is the full story.

There are two variables involved in compensating for declination when using map and compass. The first variable is whether your declination is to the east or west of true north. The second variable is whether you are starting with a bearing on the map and converting that to your compass, or are you starting with a bearing determined by your compass and translating that on to a map. I have found that I use the first technique much more commonly than the second.

Converting a Map Bearing to a Magnetic Bearing

The first step in compensating for declination is to determine the declination for your area. This can be done with address or zip code at this NOAA webpage.

A very common technique for determining a direction you want to travel is to look at two points on a map. The first point is usually where you are currently located, and the second point is your intended destination. A true bearing (relative to true north) is determined by placing the compass on a line drawn between the two points. It is important to ensure that the compass is pointing in the direction you intend to travel — I have seen too many mistakes made by placing the compass carelessly on the map only to find it was reversed.

Once the compass is aligned with your intended direction of travel, turn the bezel so that the orienting lines end up aligned north/south, ensuring the north (or N on the compass) is pointing north on the map. You can now read the true bearing at the mark on the compass bezel. It is important to remember that this reading is a true bearing. If declination is to the west, you add the value of the declination to your true bearing, and the sum is your magnetic bearing. If declination is to the east, you subtract the amount of declination from your true bearing, and the result is your magnetic bearing. You can then set the compass to the magnetic bearing and follow it toward your destination.

What If I Can Preset the Declination on My Compass?

If you have a compass that has the ability to preset the declination, this feature is most convenient when you are working in an area where declination is constant (e.g. in one county for a few years). Ensure that the compass is preset to the declination for your area. In the steps above, once you have turned the orienting lines to north/south on the map, the compass is then set with the magnetic bearing, so there is no need to do the additional math to compensate for the declination since that has already been preset.

Summary

The concept of declination has confused the best of us navigators. It is the angle of difference between the geographic north pole and the magnetic north pole and is measured in degrees from your location on the planet. It can change over time, but slowly. There are several ways to compensate for declination when using a compass and map. Be careful about applying these concepts, and you should be good to go enjoy the outdoors.

Rob Speiden is a professional search and rescue volunteer who has participated in over 330 searches since 1993. He teaches land navigation, tracking and other SAR classes for both the Virginia Department of Emergency Management and his own Natural Awareness Tracking School. Rob has written two books on tracking humans for SAR: “Foundations for Awareness, Signcutting and Tracking” and “Tracker Training.” More information about Rob’s books and classes can be found at www.trackingschool.com.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices