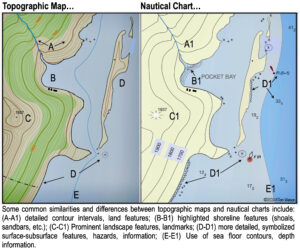

Even in this tech age of global positioning devices and other cellphone-assessable electronic navigational software, the use of traditional maps and charts is still relevant, especially for those exploring major inland lakes, rivers and coastal shorelines by small, muscle-powered watercraft. Although it’s quite common to hear someone toss the terms “map” and “chart” around indiscriminately, they provide distinct and often different information to the user.

A nautical chart shows hydrographic data — specific, detailed information on shoreline characteristics, water depth, tide predictions and myriad other structures and obstructions to navigation (reefs, shoals, sub-surface rocks, etc.).

Topographic maps (topos), show land features, attractions, and what other in-formation the map producer wants to convey. Like road maps and atlases, they use var-ious geographic and cartographic references and other topographic information.

Based on those definitions, a “chart” is a mariner’s navigational tool for plotting courses across open bodies of water or in high-traffic commercial waterways, and are considered as serious tools of navigation. “Maps” are more of a reference guide denoting roads, trails, mountains, etc. and other general information – but not necessarily de-tails about the condition of such features.

Illustration by Tom Watson

Today, nautical charts are either printed on paper using traditions symbols and reference information or digital raster image equivalents which enables the chart user to link to detailed electronically-displayed information via symbols on the chart. Nautical charts are available for all U.S. waters, including territories and the Great Lakes.

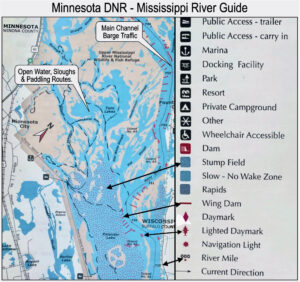

Many states along the Mississippi River also produce sectional, milepost-type maps of river corridors showing myriad features and hazards such as main channel routes, sloughs, wing dams and stump fields.

Illustration by Tom Watson

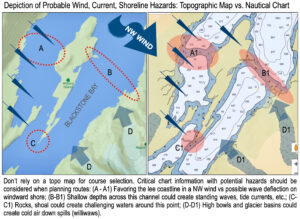

Topo maps are quite often used inland to define trails, notable land forms and other ground features that help direct the user along chosen routes. Nav’ charts provide critical information, especially for coastal, in-shore kayakers: water depths, shoals, kelp beds, reefs, submerged rocks, tide currents and other potential physical hazards and ob-structions, many of which can affect the condition of the waters when encountering winds and tide currents.

A case in point might be when determining which water passage to take around an island or point. A topo’ map will only show the shoreline, possibly a general depth contour right along shore but nothing else. The nautical chart, in addition to basic land contours along the coastline, will reveal the location of rocks below the surface (useful for determining if their alignment could create standing waves depending on the timing of the tides). Locations of hazards/obstructions such as shoals, reefs, depths, buoys, plus other critical information makes the chart the better reference when navigating along an unfamiliar coastline.

Illustration by Tom Watson

A decision to also use a topo for on-water navigation may be to better determine if a landmass might warn of a possible ‘williwaw’ wind spilling out from shore, or if steep, water’s-edge rock walls might cause hazardous reflections of waves against the shoreline (clipotis).

A prudent small-craft boater should carry the appropriate charts and maps to help safely navigate your chosen waterway.

If your high-tech GPS or navigation app fails, it’s good to know that a trusty chart/map is reliable backup.

Tom Watson is an award-winning outdoor safety and skills columnist and author of guide books on tent camping, hiking and self-reliant survival techniques. His website is www.TomOutdoors.com.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices