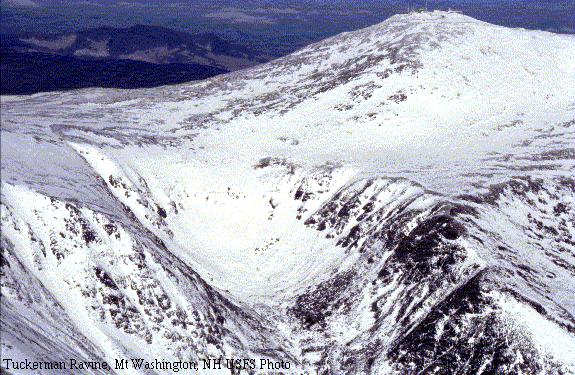

Tuckerman Ravine, the cirque in the center, attracts skiers, snowboarders, and the like who hike up to ski and ride its steep terrain.

The spring skiing season is in full swing on New Hampshire’s Mount Washington. Skiers, snowboarders, sledders, hikers, dogs, snowshoers, and more are all a colorful cast of characters in the White Mountains’ conga line that strings out from the floor of hallowed Tuckerman Ravine.

With packs on backs, they make the annual pilgrimage from the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Pinkham Notch Visitor Center to the wondrous glacial cirque on the mountain’s eastern flank lined with steep chutes, gullies, and wide tantalizing bowl to slide in the shadows of skiing pioneers like Dartmouth’s John Carleton and Charley Proctor, who are credited with first skiing the Headwall on April 11, 1931. They ski in the spirit of American Inferno race winners Hollis Philips, Dick Durrance and Toni Matt. It was Matt who on April 16, 1939 made his record incendiary run in the last American Inferno race from the summit, over the Headwall, and down the Sherburne Trail in a mind-blowing 6 minutes, 29.2 seconds.

It is New England’s spring rite of passage, with the bowl often containing snow through spring and into summer.

Despite the camaraderie, days of sun, and luscious corn snow, Tuck’s is also a dangerous place. People die, from those who appear like clowns in the mile-high alpine circus to the most thoughtful and experienced of outdoor enthusiasts.

The YouTube video below shows a skier doing a face first fall and slide down a steep run (warning–the video contains some rough language).

httpv://youtu.be/rjTmE4nMjJ4

The key to a safe trip is knowing before you go. Do your homework, choose the right gear, and be flexible.

Remember spring means the mountain is loaded with quick-changing hazards and weather. There are some safety checks out there. United States Forest Service Snow Rangers work the ravine and post avalanche advisories available online through the Mount Washington Avalanche Center website.

Though skiers, riders, and climbers are in charge of their own safety, the Mount Washington Volunteer Ski Patrol has members in the ravine. Near the ravine at Hermit Lake (a.k.a. Hojo’s), the Appalachian Mountain Club caretaker also has vital information on conditions.

Avalanches do occur in the ravine. They can happen naturally or triggered by people. There are also falling skiers and riders, often with gear flailing (thus the cry “yard sale” from the peanut galleries).

Snow rangers are quick to offer these tips:

- Potential for falling ice. Many people have been hurt or killed by icefall in the ravine. With many chutes and rock formations given names, rangers say popular Lunch Rocks is not a safe place to sit and watch. They suggest the left or south side of the ravine as a better station.

- Watch for crevasses and waterfall holes. If you know where they are, avoid them. You can do this by climbing where you plan to ski down. The Lip and Center Bowl tend to hold the most serious threats. You can also break through a weak snow bridge.

- Look out for undermined snow. This is problem comes as the snowpack drops. Several gullies have running water under them. So depending on thickness, you can plunge into a channel of icy water.

On the avalanche bulletins, rangers post this information:

- Safe travel in avalanche terrain requires training and experience. This advisory is just one tool to help you make your own decisions in avalanche terrain. You control your own risk by choosing where, when, and how you travel.

- Anticipate a changing avalanche danger when actual weather differs from the higher summits forecast.

So be smart and well-informed before making the trip.

First image is a USFS photo and is in the public domain, second image by Msheppard via Wikimedia Commons

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices

The

The