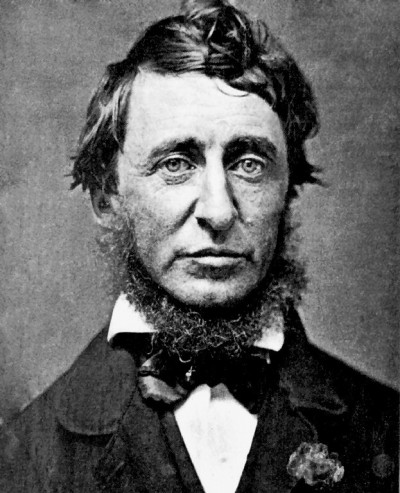

Henry David Thoreau

An act of civil disobedience in a California wilderness probably would have sat well with Henry David Thoreau.

And if a group of writers and environmentalists has its way, an unnamed 12,691-foot rugged peak in the John Muir Wilderness would officially be called Mount Thoreau.

Locals call it that, but that’s about it. Unnamed natural features must stay that way in federal wilderness areas, the government has stated, though there are rare special exceptions made.

Regardless, on September 26, 11 Thoreau aficionados including science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson and Zen Buddhist poet Gary Snyder hiked up the Sierra mountain for a brief ceremony to dub the peak “Mount Thoreau.”

The peak towers above Piute Pass and several bodies of water including Emerson Lake, named after fellow transcendentalist 19th-century writer and friend Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Many a hiker has walked in Thoreau’s footsteps and his writings have become inspirational to lovers of the outdoors. The “father of environmentalism” perhaps best known for this two-year stay on Walden Pond in Massachusetts outside Boston where he sought a simple life, was not only a land surveyor but also a keen hiker exploring vast areas of New England. From Mount Katahdin in Maine’s remote Baxter State Park to the solid peaks of New Hampshire’s White Mountains to rambling the woodlands of Massachusetts, he explored it all.

“I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits unless I spend four hours a day at least—and it is commonly more than that—sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements,” Thoreau wrote in an essay called “Walking.”

It was Thoreau’s connection to Katahdin that proved inspirational to Robinson during a snowshoe trip he took with a friend. Thoreau had climbed Katahdin in the 1840s and it made such an impact on him that he started a call for the creation of a national park system.

“Why should not we, who have renounced the king’s authority, have our national preserves, where no villages need be destroyed, in which the bear and panther, and some even of the hunter race, may still exist, and not be civilized off the face of the earth,” he wrote in “The Maine Woods.”

A spring on the flat plain-like Tableland of Katahdin is named after Thoreau. But Robinson felt the writer should have a mountain named after him.

According to The New York Times, Robinson carried a small register and journal to the top of the mountain during the late September hike. After the climb, the group had a symposium on Thoreau and the mountains.

As to whether the name “Mount Thoreau” will be officially recognized, only time will tell.

“I know there are some mountaineering groups that do start calling features certain names,” Lou Yost, executive secretary of the Board on Geographic Names, part of the United States Geological Survey, told the Times. “The board’s stand is that it doesn’t know anything about these.”

The Times said at the symposium following the climb, Robinson noted Thoreau’s influence on John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club and for whom the wilderness itself was named.

Science fiction writer and college professor Paul Park said he was particularly struck by Thoreau’s descriptions of achieving a mountain summit.

“There’s a section that consists of precise observations of different kinds, and then gradually it’s as if he moves upward to a place where he completely loses it,” he told the paper. “That’s often a place where you can see that the observations he’s made on the climb become the matrix for this expression of pure feeling, not even ideas.”

Image courtesy of Christophe Marcheux/Wikimedia Commons

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices

The

The